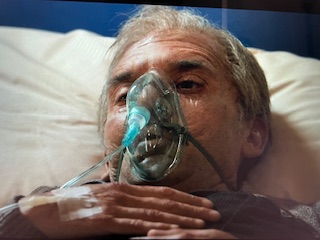

Directors Fabio Grassadonia and Antonio Piazza, who directed “Sicilian Ghost Story” in 2017, return to the 60th Chicago International Film Festival with “Sicilian Letters,” the story of an attempt to capture real-life Mafia crime boss Matteo Messina Denaro. The crime boss known as the last godfather was hunted for 30 years and was finally captured on January 16, 2023, outside a medical facility in Palermo where he was seeking treatment for colon cancer under an assumed name. Over 100 police were involved in his apprehension that day. He was transferred to a prison with a cancer medical facility, where he died 8 months later (September 25, 2023), after slipping into a coma on September 24, 2023. At the time of his death, aged 61, it was estimated that Matteo—who had been sentenced to life in prison in absentia for the death of Giuseppe DiMatteo in 2012—was worth 4 billion dollars.

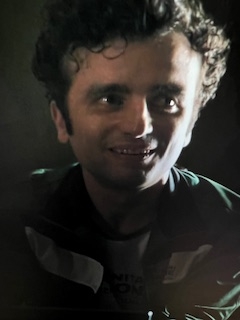

Matteo, portrayed by Elio Germano, was known to be a cold-blooded adversary. He once killed a rival (Vincenzo Milaggo from Alcamo) and then strangled the man’s pregnant girlfriend. Matteo had been familiar with guns since the age of 14. At one point, he tells the woman harboring him (Lucia Rasso, played by Barbora Bobulova) that he was responsible for avenging her husband’s death and that he murdered the killer when he was only 17. Matteo also bragged, “I filled a cemetery all by myself.”

Don Ciccio takes his three children to kill a goat for the holiday meal in “Sicilian Letters.”

We see this early descent into savagery in the film’s opening scene, when Matteo steps up to murder a goat under the direction of his father, upstaging his older brother and foiling the attempts of his sister to grab the knife herself. Matteo’s father, Francesco Messina Denaro, known as Don Ciccio, died in November of 1998. By then, Matteo had been on the FBI’s Most Wanted list for 5 years, after a string of bombings in 1993 that killed two prosecutors, Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino.

PLOT

The film begins by saying “Reality is a point of departure, not a destination.” In other words, as with most films, a certain amount of poetic license has been taken with real life. But, as Director Antonio Piazza told me in a conversation on August 20th, most of the story is true and accurate. In order to capture the last godfather, the police attempt to turn the former Mayor and Headmaster Catello Palumbo (Toni Servillo), who was Matteo’s godfather. Catillo has just spent 6 years in Cuneo prison. The police tell him, “Our meeting is your chance to get back in the game.” They want him to help capture the arch-criminal, who has been on the loose for 30 years.

Catallo with the illegitimate son of the Mafia don, taking him to meet his father for the first time. (“Sicilian Letters”).

Catello—an odd-looking individual with his comb-over hairdo—has returned to his long-suffering wife Elvira, who seems to take a dim view of her spouse. Catello’s hotel project is in jeopardy; it’s illegal because it’s in a nature preserve. His wife, Elvira (Betty Pedrazzi), is fed up with the circumstances the family has been reduced to during Catello’s incarceration. His daughter Letizia (Dalila Reas) is pregnant by the janitor at Catello’s old school, (a part well-played by Giuseppe Tantillo as the “simple and sweet” Pino Turino.) Elvira does a good job of defending Pino from Catello’s put-downs, but there are other instances in the screenplay where women are demeaned, but none stand up to their abuser. It was definitely a sign of those 2000 times. One such scene has a male investigator, Captain Schiavon (FaustoRussi Alessi) screaming in the face of female investigator Rita Mancuso (Daniela Marra). She seems unhappy about it, but she says nothing. The scripted line that sums up women 25 years ago (and more): “It’s the men who make decisions at home.” Indeed. I remember those days well.

The police embrace Catello’s idea of using letters to ferret out Matteo’s location. The letters—known as pizzini—were small folded-up notes used to communicate with other members of the Cosa Nostra in order to avoid phone conversations. They look very quaint in the era of e-mail and pagers blowing up in Gaza. The pizzini reminds me of notes passed from student to student in schools from the forties through the sixties, now an anachronism. The idea is to use Catello’s relationship with Matteo and the trust Matteo might have in Catello to “Let him hear his father’s voice from beyond the grave.” It seems to work—or does it?

TRUST & CORRUPTION

Investigator Rita Mancuso (Daniela Marra) and Catella Polumba (Toni Servillo) working together to apprehend Matteo Messina Denaro in “Sicilian Letters” at the 60th Chicago International Film Festival.

The issue of trust was huge in the film. One scripted line, “In this village we all spy on one another.” Matteo at one point executes a friend (Nando) who is suspected of stealing cocaine and tells him at the moment of truth that the issue is not the value of the drugs but that “It’s an issue of trust.” The female investigator Rita Mancuso (Daniela Marra) early in the investigation tells Catello not to trust the other investigators on the case. She suspects (correctly) that there is so much corruption that the police don’t really want to catch Matteo. Sicilian singer-songwriter Colapesce even composed a song for the film, “La mal vagita seve al mondo intero” which means “evil serves a purpose for the entire world.” Matteo is the center of an entire world using him for their own greedy purpose.

THE GOOD

Catallo Palumbo (Toni Servillo) faces down Matteo Messina Denaro (Elio Germano) face off in “Sicilian Letters” at the 60th Chicago International Film Festival.

The plot is complicated and there are quite a few characters to follow. The acting is compelling. Elio Germano, who plays Matteo, actually moved to Palermo for a short period of time to pick up the dialect and the culture (and some Sicilian mannerisms). The part of Catello’s wife (Elvira) was particularly interesting. She was one woman of the era who spoke up. Elvira seems very fed-up with her ex-convict husband and says so. The comic touches help lighten the mood, as when we learn that Catello’s nickname is “Straight-shitter,” which has to do with the circumstances of his arrest. Some found Catello’s odd hair-do and the comic touches distracting, but they were well-done and necessary to prevent a grim film from becoming too depressing. There is the jab at Matteo’s sister’s Taralli, a pastry that Matteo warns is as hard as cement. The cinematography and music also served the film well.

SPEAKING WITH DIRECTOR ANTONIO PIAZZA

Writer/Director of “Sicilian Letters” Antonio Piazza.

The significance of the small statue called “Pupu,” described as being the most valuable in the town’s small museum, was explained to me by the director, Antonio Piazza. Not only is it true that the statue was very valuable, but it demonstrated how the Mafiosa ripped off antiquities of the country for their own benefit. As Director Piazza explained, the word has different meanings in Sicilian. It can mean “puppet” and it can mean “child.” Said Antonio, “In a way, Matteo is a puppet and a child.” The director explained that the existence of the “Pupu” statue was absolutely true. As Director Piazza noted, “Reading the notes left behind in Matteo’s hide-out and seeing the personal items left behind opened up a whole world to us.” Assembling jig-saw puzzles in Matteo’s hide-away was one way he passed the time while hiding out for 30 years. As in the movie, said Piazza, the real Matteo actually did write a letter to the puzzle manufacturer complaining about a missing puzzle piece. Matteo also read voraciously in hiding and watched such television shows on DVR as “The Sopranos” and “Sex and the City,” plus reading an Andre Agassi book, Baudelaire, and Dostoyevsky.

CHARACTERS

Giuseppe Tantillo portrays Pino Tumino, the only pure character in “Sicilian Letters,” says Writer/Director Antonio Piazza on October 20, 2024 in Chicago.

“Pino Turino (Guiseppe Tantillo), who is married to Catello’s daughter, is the only character in the movie who comes out pure,” said Antonio Piazza. “Somehow he was able to read the context, which protected him morally.” Police investigator Rita Mancuso, Antonio explained, “really wants to capture the fugitive. She’s honest and idealistic but blinded by her obsession with capturing Matteo.” Asked about the accuracy of other names in the film, Antonio said that only Matteo’s name was true to life; most others were changed. We discussed the state of women at this time in history and in the world. Antonio agreed that Matteo’s sister would have been angry that she was a woman living in a man’s world at a time when, as the script says, “It’s the men who make decisions at home.” This second-class citizenship may also have contributed to Rita Mancuso’s perpetually dour and hostile outlook.

Don Ciccio, Matteo’s father, died in 1998–a point at which his son had been on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted List for 5 years.

Matteo was very close to his father, who died in 1998. However, his father was not the womanizer that Matteo chose to be. One small change that Director Piazza acknowledged was that the illegitimate child is said to be a son. In reality, the child who wrote the Father’s Day essay about her MIA father was a girl. Matteo’s sister really did feel that Matteo should acknowledge his daughter, but the film—with its father-and-son dynamic—worked better with the child being male. The second-class citizenship of girls is made clear from the opening scene of the three children with their father and the goat. I asked if the sunglasses perched on the small child’s head (Matteo’s illegitimate son Gaetano, in the film) were meant to show a passing of the torch to the next generation in the film. Director Piazza acknowledged that the RayBan sunglasses were definitely Matteo’ signature and became iconic. Photos of Matteo on driver’s licenses, old and young, show him wearing RayBan sunglasses. (Think Tom Cruise in “Risky Business.”)

CONCLUSION

The primary themes of “Sicilian Letters” concern evil, corruption, and trust. Writer/Director Antonio Piazza at the 60th Chicago International Film Festival on October 20th said, “Your reading of the film is very much true. We are asking the audience, ‘How is all this possible?’” This continued exploration of Cosa Nostra in Sicily and the 30-year search for Matteo Messina Denaro, the last godfather, was an engrossing, well-written, well-plotted, well-acted and well-directed outing which I thoroughly enjoyed.